Brooks Williams

American Guitarslinger

down Home in the U.K.

By Richard Cuccaro

Photo: Debbie Scanlon

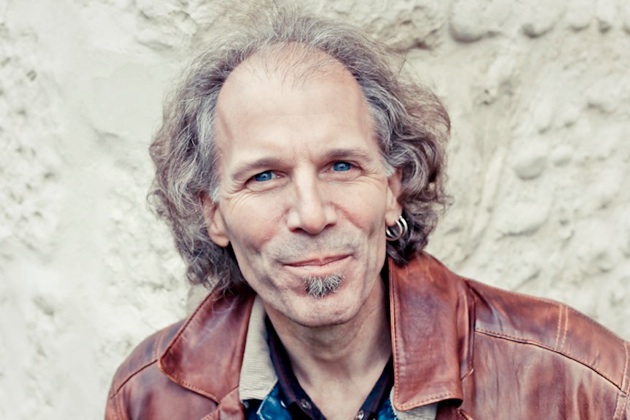

You can say the word “gifted” in a lot of languages. You’d need to know a lot of those ways if you were to count the places Brooks Williams has been referred to in that manner. Let’s just say he gets around.

His reputation as a monster acoustic guitarist is set in stone. It’s no wonder he generates statements like these — from Dirty Linen: “One of America’s musical treasures” and from an unnamed source: “…walking the line between blues and Americana, he is ranked one of the world’s top 100 acoustic guitarists.” We know, we know; it’s all subjective. When “best of” lists are posted, outraged responses usually run along the lines of: “How could you NOT put John Renbourn on that list?!” Or, “WHAT is Bob Dylan doing on that list?!” Or “You have Tommy Emmanuel ranked too low…” and on and on.

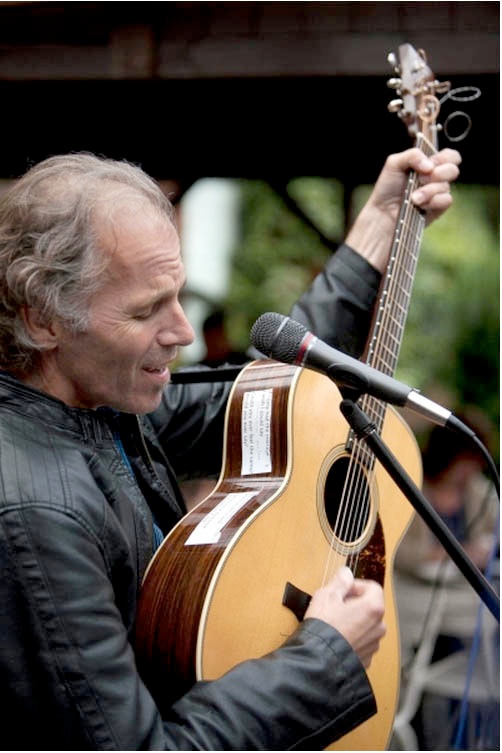

Anyway, we stand our ground on Brooks. If you watch a YouTube video like his version of “Weeping Willow Blues,” recorded at Uncle Calvin’s in Dallas, the guitar seems like it’s been grafted onto him. If further proof of his prowess is needed, in another video, apparently from the same set, he laughingly tosses off a guitar medley of the most famous rock and folk riffs. Then, there’s that voice and those songs. Don’t get me started … oh, yeah … I already have.

Every time I’ve seen him live over the years, I’ve chided myself for not having remembered to grab him for a feature article. With the release of his new CD, appropriately named New Everything, we’re finally getting that corrected.

Brooks has been living in England with his wife, Jo, who is British, for four years at this point. Jo is an MC at several British folk festivals and met Brooks at one of them. They hit it off immediately, but didn’t see each other for another year, so their relationship developed “at a slow burn,” he said. After marrying and trying to split time between the U.S. and the U.K., they finally just settled in England.

Speaking with Brooks from “across the pond,” I found someone who is so acclimated in his new life that he speaks in a clipped, slightly British, almost Cockney manner, sort of like the way a Northern visitor to the U.S. Southern states might return northward, dragging the expression “y’all” across the Mason-Dixon Line.

Beginnings

Brooks was born in Statesboro, Ga., in 1958 and raised in a whole lot of other places. His father was a restless mix of Episcopalian minister and lawyer. He would get tired of one line of work or things would get slow and he’d switch back and forth. They were always on the move. “We were never in one place more than two years,” Brooks said.

Following his mother’s wishes, he took violin lessons. Whenever they got to a new town, the first thing she’d do was call a music school or store and ask who taught violin. Brooks never rebelled. The violin practice and concerts brought him in contact with other youngsters, so early on, it was fun.

Like most who become professionals, Brooks had a wide foundation for his music. “I was in a children’s choral group for a few years; did musical theater; all the while, and on my own, playing ukulele, piano and guitar,” he recalled.

At 10 years old, Brooks was a violin student in a summer program at a music school. He noticed that not many other boys his age were inside on sunny summer days playing violin. Bored with playing classical pieces and with the instrument itself, he wandered off and came across an older boy, a teenager, playing guitar. He thought, “I want to do that.” Brooks returned the next day and asked the boy to show him how to play. It took some pestering but finally he wrote some chord diagrams for Brooks to use. At first, Brooks practiced what he was shown on a ukulele they had at home. “It was similar-ish,” he said. He worked on his mother to get a guitar. She gave in, but only if he promised he wouldn’t give up the violin. While he immediately felt at home with the guitar, he kept that promise for four more years. His mother approvingly noticed that he was enthusiastic about guitar — the violin, not so much.

When Brooks was young, the transistor radio was still part of the culture. He remembered: “I listened to whatever was on the radio until I got to high school. I was one of those kids that constantly had a radio with him. I listened to Top 40, rock, anything and everything. When I got to high school I discovered albums and the whole thing just kicked wide open. I listened to it all — rock, blues, singer-songwriter (lots of singer-songwriters!), even prog rock and new wave.”

Brooks was, at his core, shy and very lonely. The guitar became his companion. It kept him away from the drinking and racial conflicts that pervaded the lives of many Southern teenagers.

Brooks developed his guitar chops playing along to songs on records and the radio. He began noticing the records his older brothers owned. He also bought a book of the greatest hits of the ’70s — Beatles, Carly Simon, CSNY, Arlo Guthrie — and it showed him how to play chords. During the last two years of high school, he played guitar constantly. Brooks’ first time playing guitar in front of an audience was in a concert on his last day of high school. He was really nervous, “shaking in my boots,” he said, but he loved the experience and was determined to do more of it.

College

Brooks went to Boston to go to college. Rather than accept an offer from Berkelee School of Music, he attended a liberal arts school for a couple of years. He left for another couple of years, but went back and re-enrolled, this time at Salem State College in Massachusetts and graduated with a B.A in English.

It was in Boston that he first heard the mix of folk, Celtic and singer/songwriter genres that he would make his repertoire and began playing out. He recalled: “I moved to Boston in my late teens and discovered acoustic music for real. I played anywhere that would have me — cafes, bars, open mics — and lots of restaurants. I played for free food! When I finally got it together enough to make a little money from playing — and I decided that’s what I wanted to do — I was playing five to six nights a week in the little clubs, bars and coffeehouse of New York and New England. The midweek gigs were in loud bars where I could barely even hear myself and I played for four hours without stopping. The weekend gigs were in quiet coffeehouses where audiences hung on every riff and lyric. I learned my trade in between these two extremes.”

Brooks got his first good guitar around this time — a Guild. At this point, he felt thrilled with his new instrument and was on his way. He’d do 15- to 20-minute sets and once in a while get his own night. During this time, in the late ’80s, stalwarts such as Vance Gilbert, Ellis Paul, Jonatha Brooke and Catie Curtis were beginning to make their mark. There were times when he’d share the stage with them in groups of two or three, introduced together as “some of the new faces in the Boston music scene.”

The Career

Asked to state some of the turning points in his career, Brooks included:

• making my first record and getting asked to be interviewed on National Public Radio’s “All Things Considered”

• signing with Green Linnet Records

-

•playing the Winnipeg, Newport and Falcon Ridge Folk festivals all in

one summer

• recording my first solo guitar record and being asked to teach guitar workshops

• discovering an audience overseas, especially the U.K.

• discovering that my music is roots music and diving into those American roots in my playing, singing and, most importantly, my songwriting

-

•being named one of the Top 100 Acoustic Guitarists.

Brooks appeared a couple of times at The Fast Folk Cafe in the mid-’90s, where I was a volunteer manager. His first appearance was on a co-bill with Frank Christian. Given that Frank was a close friend to the legendary Dave Van Ronk, Dave came to the show. Brooks said he was “in awe.” Frank was a damn fine picker himself, so the evening was a thrill. In addition to all the guitar pyrotechnics, I came away with the indelible image of Brooks cleverly easing forward and using the mic stand as a slide at the finish of one song. Feeding a habit I started at the Cafe, I bought CDs from Brooks and had him autograph them.

In addition to New Everything, which he mailed to me, I remembered owning How the Night Time Sings (1991) and Knife Edge (1996). A check of our CD shelves uncovered a forgotten treasure trove: Red Guitar Plays Blue (1994), Nectar (2003) and Live Solo (2004). It doesn’t come close to covering the 20 albums he’s issued, but it’s a start.

Red Guitar Plays Blue is a self-issued collection of vintage recordings of songs written during 1986 and 1987. It carried me back in time to when Brooks’ jackhammer-steady rhythm and pristine clear picking were a new revelation. On top of that, he sang and played so fluidly, everything swung. As I listen to “Jericho,” I’m entranced by the beauty of its slide work. Red Guitar Plays Blue is out of print and I don’t see it in the iTunes store, so I feel pretty lucky to have it. Looking at the “Listeners Also Bought” thumbnails in the iTunes store below Brooks’ albums, one sees Kelly Joe Phelps, Taj Mahal, Susan Tedeschi and Muddy Waters. You get the point.

The early albums tend to show Brooks unadorned, just him and his guitar. Knife Edge illustrates Brooks’ love for Ireland in the rollicking instrumental track “Belfast Blues” and the stomping slide romp “Rotterdam Bar,” which recounts the time he played Belfast’s legendary Rotterdam Bar alone on stage to an empty room after it had been closed down (a favorite player’s venue during the ’90s, an Internet search as to whether it was saved from demolition is inconclusive). The title track invites the female listener to walk with him on the insecure “knife edge” of a relationship. It presents the image of the guitarist as world-traveling romancer.

One instrumental track on How the Night Time Sings, “Look What the Cat Dragged In,” is itself cat-like, aurally walking the top edge of a fence and nimbly leaping from one tiny surface to another.

The opening instrumental track of Live Solo, “Chasing The Groove,” is typical Brooks — a bouncing fret-skipper that easily beguiles the audience who will now hang on every note and syllable of the evening’s performance.

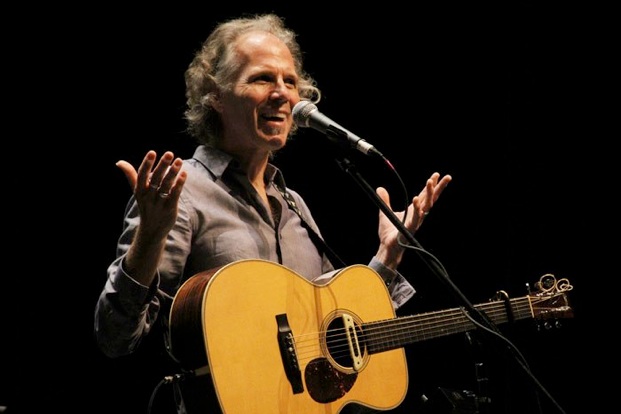

His new CD, appropriately named New Everything, is at times a good-time, jump-out-of-your-seat, get-up-and-dance guitar clinic. At some points, it turns pensive. Brooks intends it as a portrayal of a series of short stories. In the liner notes, each track has a snippet of wry commentary.

When he lights into “Deep River Blues,” the classic made famous by Doc Watson, my body does a giddy flinch of joy. He plays fingerstyle on a resonator guitar while Martin Simpson, British guitar monster, adds background slide licks on a second resonator. The accompanying liner remark? She was having a fine time until she heard the line about the waterfowl.

The title track is a skewed version of the old country song “Flowers on the Wall,” by The Statler Brothers (“countin’ flowers on the wall, that don’t bother me at all”). The guy has lost his woman, but is trying to put on a brave front, telling everybody about all the new stuff in his life You’re there with your friends, I’m here with mine / You’ve found another guy, I’m doing fine … As a counterpoint to emphasize the B.S., Brooks uses a bouncy style similar to Marshall Crenshaw. “It’s so nice to hear how well it’s all going for you,” he said, not quite hiding the irony in his voice.

“Moon Over Maverick” is mainly an ode to Michael Terry, a former manager of Uncle Calvin’s in Dallas. Maverick is an Americana festival held every year in eastern England during the 4th of July weekend. Jo and Brooks live nearby. They returned home one night after a busy, blissful day for Brooks. On the drive home, a full moon hung in the sky and awoke reminiscences of people who weren’t there that day, specifically Michael, who had passed away. Michael had a habit of helping singer/songwriters. He gave Brooks a fresh push back in the early 2000s, lining up gigs in numerous venues, when Brooks was struggling. He got Brooks to see that music was a part of him and nothing he could walk away from. Over a soft strum, the song’s lilting melody is reminiscent of “Moon River.” There’s a great big world for you to see / so get along, don’t worry about me… It was a long ol’ drive, but the look on their faces when they got there was worth every mile.

“Son of a Gun,” with its throbbing beat and fingerpicking, has an early Elvis Sun Music feel. It’s about a guy who blames everyone else for the trouble he gets into. There goes the door, breakin’ the chain / knockin’ the chair to the floor / kickin’ the whole thing off… It was on fire when I got here. That’s what he told the police.

This batch of stories reflects his expressed career goal to continue following the primal urge to express reactions to life events with sung poetry and a guitar riff. Or two. Or two dozen.

Brooks is quick to remark how welcome and appreciative his British audiences have been and continue to be. However, he admits to getting homesick at times. So he looks forward to the tours that take him to America. There’s one happening right now and we’re eager to welcome him home.

Website: www.brookswilliams.com

Upcoming performances include:

Nov 1 Caffe Lena, Saratoga Springs, NY

2 Ripton Community Coffee House, Ripton, VT

3 2pm University Café, Stonybrook, NY Co-bill with Beaucoup Blue

8,9 Northeast Regional Folk Alliance (NERFA), Kerhonkson, NY Selected Quad Showcase plus Acoustic Live guerrilla showcase late Friday 12:30am